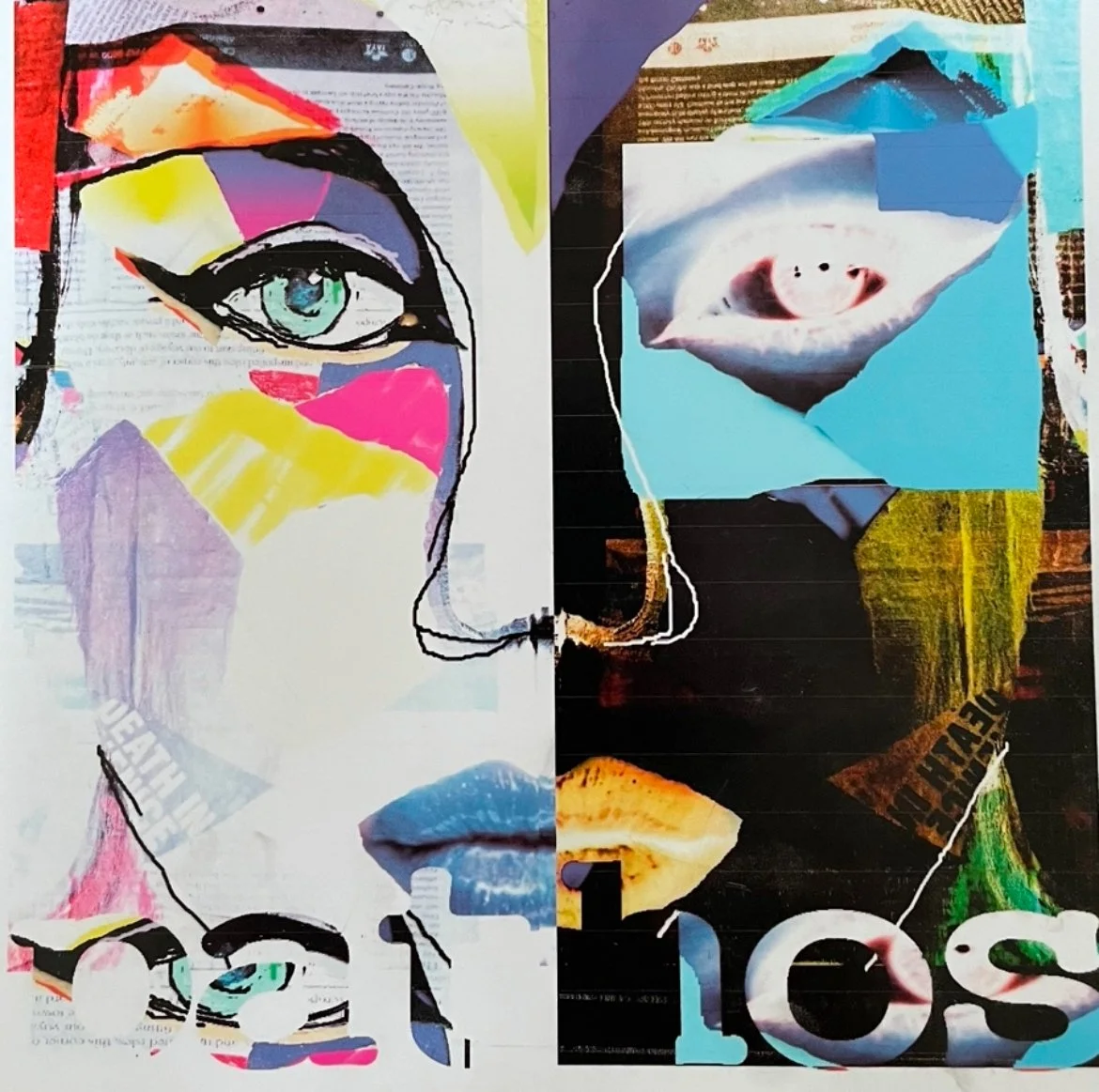

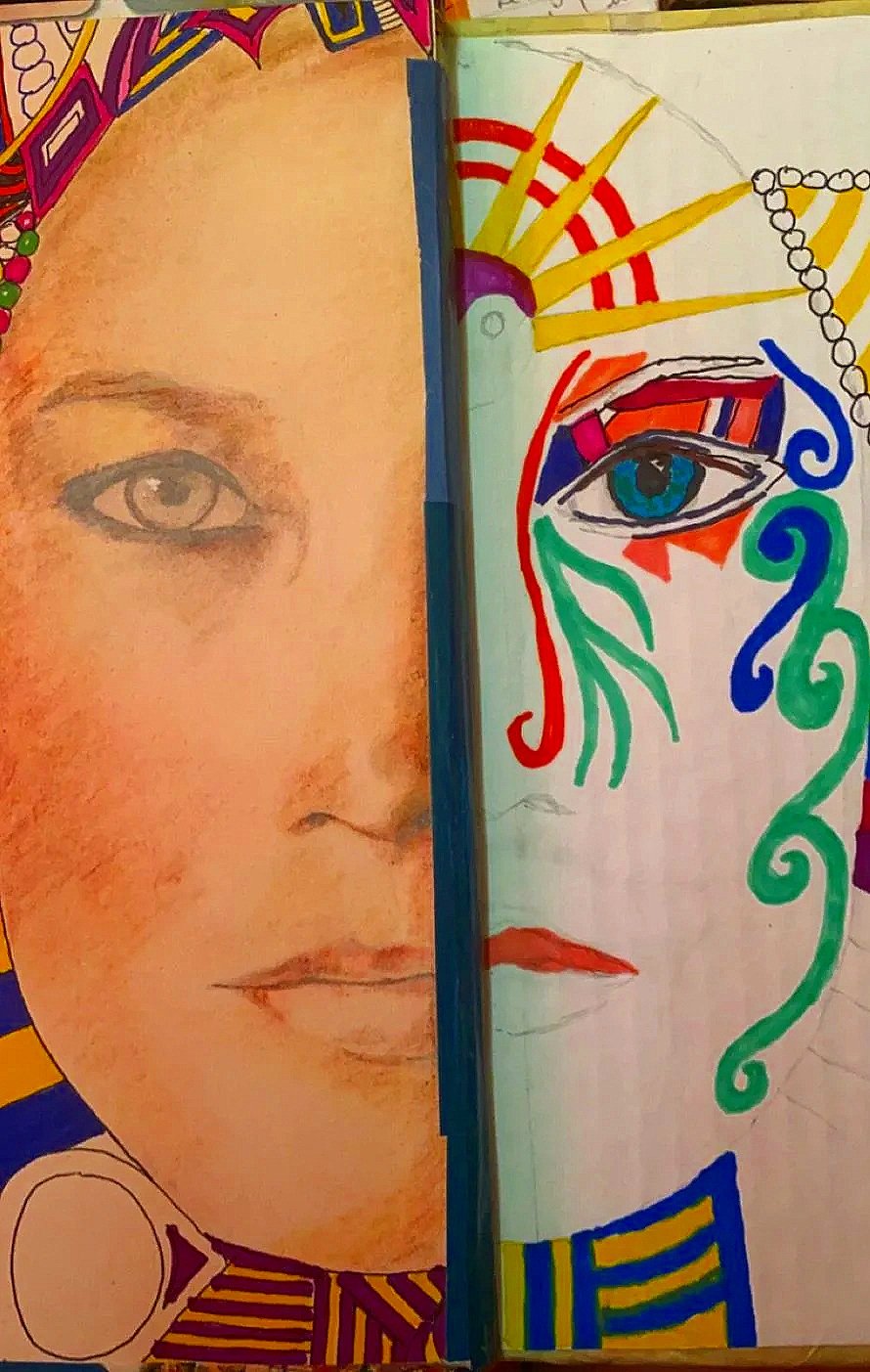

Seeing Behind the Mask

Beneath the smile, the calm, the polite nods and the cheerful “I’m fine,” lies a hidden story. Masking is part of Milly’s survival - it’s how she’s coped in a confusing, overwhelming world.

Theme: The Burnout

Quick Take:

Milly smiles, but it’s harder than it looks.

Masking takes energy no one sees.

Presence matters more than conversation.

Growing Up with Hidden Emotions

Milly has always been good at masking. Coming from a generation where talking about feelings was rare, she developed a quiet stoicism - hiding emotions as a way of coping or protecting herself. When she was tired or ill, she’d pretend she wasn’t, so she wouldn’t appear weak or let anyone down. It annoyed me growing up; I didn’t like things being hidden or not quite real.

More than Meets the Eye

What bothers me most is the confusion it causes family, friends, carers, and even medical professionals. Everyone assumes Milly is fine when she says things like, “How lovely to see you!” or “What a mess we are in!” referring to waiting lists or the war in Ukraine. She may seem normal compared with those with advanced dementia, but the reality is far more complicated.

Behind the Mask

Milly manages normal conversations through years of practice, social conditioning, and ingrained social cues. She’s mostly on autopilot, relying on responses she has spent a lifetime perfecting.

Just because she can laugh, share kindness, or offer wise comments doesn’t mean it’s easy or comfortable.

She often struggles to keep up, worrying about what she just said, what others said, and what comes next. Memory loss means she’s constantly catching up - it’s mentally and emotionally exhausting. Most interactions leave her drained.

Masking or Denial?

I didn’t initially understand the difference between denial and masking - they overlap and caused the same kind of problems but now I think of it very simply: denial is Milly’s self-protection, masking is her social protection.

Denial meant consciously shielding herself from the fear of dementia, and then it became unconscious; she blamed old age or “just being daft.”

Masking happens at the same time - pretending everything is fine while quietly wanting to withdraw from activities she used to enjoy. Most of us mask sometimes. We smile when we’re tired and nod when confused.

Even without dementia, masking takes enormous energy. One difficult day at work or the attendance of a big family event can leave us drained, irritable, and empty. It doesn’t therefore take much effort to imagine how Milly feels - all the time.

Part-time Personal Assistant

Managing friends and family felt overwhelming for her - especially when they offered care and encouragement, which became pressure.

And we had so many painful conversations, regularly going round in circles:

“What’s happening Monday?”

“It says in your diary”

“What did you arrange?”

“Nothing! YOU arranged it! You’re seeing Mary.”

“I didn’t organise it?”

“Well I wouldn’t! She’s not my pal!”

“What are we meant to be doing?”

“I don’t know. Having lunch, like you normally do.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know! I didn’t speak to her. For fun?”

“Is it her birthday or something?”

“I’ve no idea. Look in your birthday book. Or ring and check with her what’s happening.”

“Oh, just leave it.”

Taking off the mask felt impossible. She didn’t want to admit struggle, or hurt anyone. Stress caught up with her, and afterwards she always needed rest and went to bed.

I realized the only way forward was to stop swinging between frustration and diagnosis. I grudgingly accepted the role of part-time personal assistant - handling appointments, meals, supplies, and her social calendar - while giving her space to feel in control. For in-person meet-ups, I stayed involved gently, letting her lead whenever possible. Friends’ kindness sometimes stressed her, but I’m sure that at the same time their perseverance gave her a strong sense of being loved.

Presence is More Important Than Friendship

I once struggled to explain why I avoided encouraging socialising with wider family and friends. I know they sometimes found it difficult to understand - no wonder, I’m not sure I did either! But now I can explain it quite simply: a gentle, consistent presence matters more than deep friendship.

Friendships can be tricky. Milly has to work hard to follow conversations, often pretending to understand or remember, which can leave her anxious or embarrassed.

By contrast, an acquaintance or professional presence - offering simple, kind support - carries no pressure. It’s togetherness without deep conversation or shared memories, which is far more meaningful for her.

I avoid situations likely to overwhelm her; it’s tiring for both of us. Family and friends still matter, so I share messages, photos, letters, or cards at the right moment, reassuring her and moving on if they spark brief panic - “Oh, do I need to …?”

Finding the Balance

The local lunch and social club provides the best interactions - light, comforting, and predictable. The team understands dementia and lets her participate at her own pace. She can watch, join in, or simply share time with others. This suits her needs, reduces pressure, and makes socialising manageable and enjoyable.

A Simple Life

Milly now avoids most social contact. She wouldn’t attend the lunch club without gentle encouragement. Masking persists - she wants to belong and appear in control - but she still asks after people, smiles, and offers warmth.

The effort leaves her needing a couple of hours’ rest afterwards. No complaints from me - it’s a small, welcome pause in the day.

This is what care looks like for us now: quieter, smaller, and manageable.